The concept of a spherical Earth is so ingrained in our modern understanding of the world that the idea of a flat Earth seems almost absurd. Yet, for centuries, various cultures and thinkers held different beliefs about the shape of our planet. One of the most intriguing artifacts from this period is the 1587 Flat Earth Map, a document that offers a unique window into a pre-Copernican worldview.

This map, created by the English cartographer, printer, and publisher William Cuningham, is not a map of the world as we know it today. Instead, it’s a diagram illustrating the Ptolemaic model of the universe, a geocentric system where the Earth is a stationary, flat disk at the center, with the sun, moon, and planets revolving around it.

Unpacking the Map’s Features

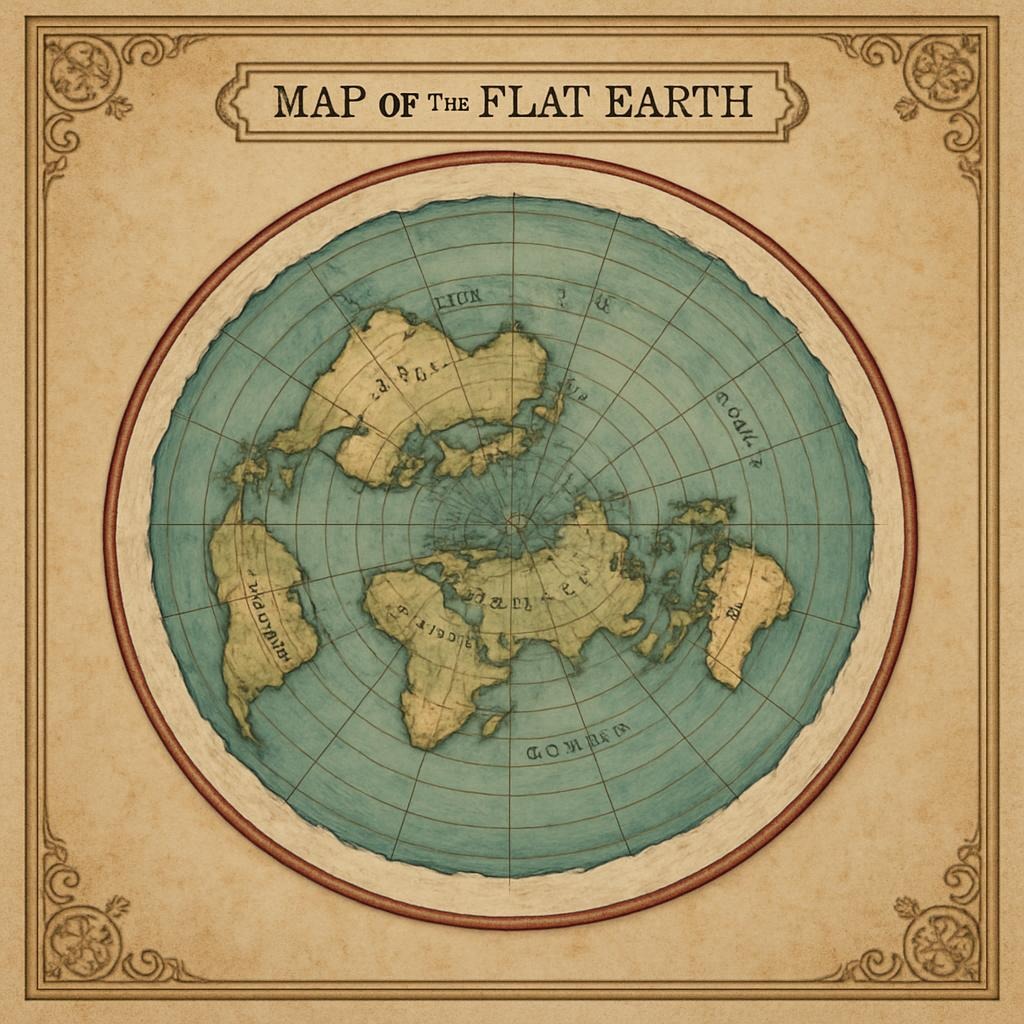

The 1587 Cuningham map is a visually rich and complex document. While it might be called a “flat earth map,” it’s more accurately a cosmological diagram. Here’s a breakdown of some of its key features:

- The Earth as a Disk: The center of the map is occupied by a flat, circular Earth. This wasn’t a representation of a known geography, but a symbolic depiction of the world’s place in the universe. The Earth is depicted as a landmass surrounded by a ring of water, consistent with many ancient cosmologies.

- The Geocentric Model: Surrounding the Earth are several concentric circles, each representing a celestial sphere. This is the heart of the Ptolemaic system. The first sphere holds the Moon, followed by Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These were the seven known “wandering stars” or planets.

- The Firmament and the Prime Mover: The outermost sphere is the “Firmament,” or the sphere of the fixed stars. This was the boundary of the known universe. Beyond this, a final sphere represents the Primum Mobile, or “Prime Mover,” a concept from ancient philosophy and theology. The Prime Mover was thought to be the divine force that set the heavens in motion. This demonstrates how deeply entwined science, philosophy, and religion were during this period.

- Zodiacal and Other Illustrations: The map is also adorned with intricate illustrations of the zodiac signs and other celestial symbols. These were not just decorative elements; they were essential for understanding the movements of the sun and planets and for astrological calculations, which were a significant part of scientific inquiry at the time.

The Context: A World on the Cusp of Change

The 1587 Flat Earth Map was created at a pivotal moment in human history. The Renaissance was in full swing, and new ideas were beginning to challenge the old order. While Cuningham’s map represents a traditional, geocentric view, it was published just decades after Copernicus had introduced his heliocentric theory, which placed the sun at the center of the solar system.

However, it’s important to remember that the heliocentric model wasn’t immediately accepted. The geocentric view had been the dominant scientific and religious paradigm for over a thousand years, supported by the writings of ancient philosophers like Aristotle and astronomers like Ptolemy. The transition from one model to the other was a long and complex process, marked by scientific debate, religious controversy, and a gradual accumulation of observational evidence.

The Cuningham map, therefore, is not a testament to a widespread belief in a flat Earth in the late 16th century. By this time, educated people, especially navigators and astronomers, largely understood the Earth to be a sphere. Instead, the map is a final, beautiful representation of a cosmology that was slowly but surely being replaced by a new, more accurate understanding of the universe. It’s a snapshot of a moment in time when two worldviews coexisted, one fading and the other on the rise.

Why the 1587 Map Matters Today

For modern audiences, the 1587 Flat Earth Map is more than a historical curiosity. It serves as a powerful reminder of several important concepts:

- The Evolution of Knowledge: It highlights how our understanding of the universe has evolved over time. Scientific progress is not a straight line; it’s a process of questioning, observing, and refining our models of the world.

- The Power of Context: It reminds us to look at historical artifacts within their proper context. Calling the map a “flat earth map” in the modern sense can be misleading. It was a representation of the dominant cosmological model of its time, not a literal belief in a pancake-shaped world.

- The Interplay of Disciplines: The map’s blend of astronomy, theology, and art showcases how interconnected these fields were in the pre-modern era.

In conclusion, the 1587 Flat Earth Map by William Cuningham is a remarkable document. It’s a final, elegant illustration of a pre-Copernican universe, a beautiful and complex artifact that speaks volumes about the history of science, the evolution of human thought, and the ever-changing quest to understand our place in the cosmos.

Leave a Reply